Union That Leads Charge for Higher Minimum Wage Asks for Exemption from the Minimum Wage

So. More then. OK. It sounds like a lot of hope. Hope that will come at young people at future generations.

Hope is not a plan.

drummerboy, remember that you can't out-think someone who isn't thinking. This is a theological argument, and not subject to reason or evidence.

Well that comment is out of left field. I just want to know what plan would work. Here I am thinking we want an economy where:

- Those who want to work can make a decent living

- Those willing to defer consumption in order to better themselves through education, or capital investment would be able to by saving

- We leave the country in better shape than we found it for our children & their children

Isn't that the goal? If you think that is some kind of "theological" argument, then I guess I'm a religious zealot.

yes, one solution is to go whole-hog laissez-faire and let the market rule. That would be a theological solution.

Exactly. I'm asking what the solutions are. I don't see where I've offered solutions on this thread.

I only get "We need to spend more!" I get it. $18 Trillion in Federal Debt with a large number of States and local Municipalities in very tenuous financial condition is not enough.

I'm simply asking: "How much would be enough?" Is it $19 Trillion? $20 Trillion? $50 Trillion? $200 Trillion? Exactly how should we spend that money and how will that get us back on a good economic path where we can leave things better rather than worse for posterity?

If one advocates "More!!!" as a general policy, but won't even take a stab at answering the above questions I would be careful about throwing around terms like "stupid" or "theological arguments" unless there is a mirror staring you in the face.

drummerboy said:

yes, one solution is to go whole-hog laissez-faire and let the market rule. That would be a theological solution.

But this is all I get. These posts are very much like Government Largesse, they give me nothing.

And you are the ones being prescriptive here. So, what is the plan?

Let me guess.

according to the little youtube I posted its not the total amount of the deficit but the percentage of GDP that is important. In it Robert Reich points out that the value of that percentage decreases when the economy grows.

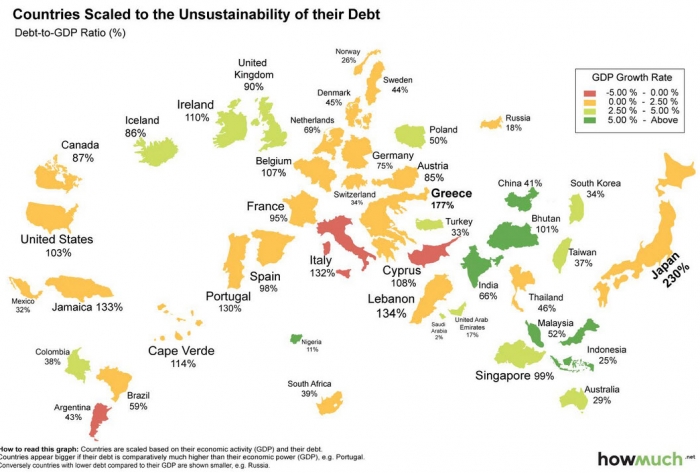

Didn't we just run this experiment, though? Compared to the US, Europe engaged in austerity in the wake of the 2008 crisis, and their recovery has been much poorer than ours. The extreme example is Greece, where austerity has been accompanied by massive unemployment.

I also saw a comment earlier by TylerDurden about a massive amount of money being printed. Doesn't libertarian economics predict that this leads to massive inflation? Why haven't we seen that kind of inflation then (and choose any measure of inflation you like, so long as you compare apples to apples - eg, whatever you believe the current inflation rate to be, also tell us what that rate, using the same measure, was when we were not printing so much money).

I don't have the data to put together a total cost, but here's my shopping list. In no particular order, spend enough to:

- Make the cost of public higher education equivalent to what it was in 1980, adjusted for inflation.

- Repair/replace the inventory of bridges that don't meet current standards.

- Invest in clean energy until it's cheaper than fossil fuels, and upgrade the energy grid to reduce the transmission loss by at least 50%.

- Refinance outstanding student debt.

- Single-payer healthcare.

- Increase teachers' salaries so that getting a master's degree is worth it.

- Upgrade and expand commuter rail in major metro areas. Increase the number and capacity of high-speed lines between them.

For a start.

We can probably pay for it all with the money we WON'T spend from a Republican president invading Iran.

hoops said:

according to the little youtube I posted its not the total amount of the deficit but the percentage of GDP that is important. In it Robert Reich points out that the value of that percentage decreases when the economy grows.

Yep.

PVW said:

Didn't we just run this experiment, though? Compared to the US, Europe engaged in austerity in the wake of the 2008 crisis, and they're recovery has been much poorer than ours. The extreme example is Greece, where austerity has been accompanied by massive unemployment.

I also saw a comment earlier by TylerDurden about a massive amount of money being printed. Doesn't libertarian economics predict that this leads to massive inflation? Why haven't we seen that kind of inflation then (and choose any measure of inflation you like, so long as you compare apples to apples - eg, whatever you believe the current inflation rate to be, also tell us what that rate, using the same measure, was when we were not printing so much money).

Did we run an experiment? So, Europe was the control group. All the economies are identical, except the US ran less austere programs. Is that it?

And what of Greece's mass austerity. Did Greece just find itself in that position? Did they just decide to go for the Austerity brass ring? Or was it decades of mis-management and corruption that got them to the point where they were broke. My wife is happy when I run up my credit cards $10 K over what I can pay that month. Of course, at some point my credit gets turned off, and she is really unhappy. Not only can I not spend that extra 10K, I have trouble getting any credit at all. Was the problem that I just stopped spending?

Just to clarify, there is no such thing as "Libertarian Economics". Libertarians believe in various things. There is a high correlation between Libertarians today and those who subscribe to the Austrian School of Economics. In regards to inflation, an Austrian will likely say that we have had massive inflation. The Austrian defines inflation as an increase in the money supply. I think you are referring to "price inflation" or the Quantity Theory of Money. The Austrians are not alone in supporting this theory in general. I think only Keynesians and perhaps Mercantalists would challenge that theory.

But, to the root of the question. There was all this money printing. So, why aren't we burning dollar bills in our furnaces? And even here, there has been a disagreement within the Austrian School. It would seem that people can't agree on anything. There were those who did expect very high price inflation(Peter Schiff chief among them) and those who were much more tempered(Marc Faber for example).

I think what is important to understand is that Austrians do not by and large believe that if you increase the money supply by X% then prices of all goods will rise by X%. It's a little more complicated than that. First, price inflation is not affected by money supply alone. Thus, in a deflationary environment, money printing may not increase prices, but many prices will likely be higher than they would have been absent the money printing.

So, what have we seen the last 7 years or so with ZIRP, global Central Bank Printing, etc. We have seen price inflation. Certainly not as high as someone like Peter Schiff predicted, and not enough to please the FOMC board. Where we have seen extremely high price inflation are the places where the money has been flowing. Financial Assets(Equities/Bonds) are at all time highs, Collectible Art at all time highs, Real Estate is in an echo bubble. If it wasn't for this monetary printing, stock prices would not have risen, hedge fund would close, Real Estate would be much more affordable, Art prices would not be at all time highs, and general prices measured by things like the CPI would most certainly be lower.

tom said:

I don't have the data to put together a total cost, but here's my shopping list. In no particular order, spend enough to:

For a start.

- Make the cost of public higher education equivalent to what it was in 1980, adjusted for inflation.

- Repair/replace the inventory of bridges that don't meet current standards.

- Invest in clean energy until it's cheaper than fossil fuels, and upgrade the energy grid to reduce the transmission loss by at least 50%.

- Refinance outstanding student debt.

- Single-payer healthcare.

- Increase teachers' salaries so that getting a master's degree is worth it.

- Upgrade and expand commuter rail in major metro areas. Increase the number and capacity of high-speed lines between them.

We can probably pay for it all with the money we WON'T spend from a Republican president invading Iran.

Thanks for the effort. Though, this just looks like a wish list of stuff you'd like to do. I'm not sure how practical it is. For instance, they have been talking about green energy and how it will become affordable soon for decades. How will this be achieved? Solar and Wind are still a very minor source of energy.

How would these "achievements" put us back on a sound economic path? Drummerboy seems to think our problem is simply the old "Animal Spirits" are keeping people from spending.

As long as definitions are fluid, it's impossible to be wrong -- you can just claim that what I call libertarianism isn't how you define it, and we can haggle back and forth and eventually just get bored or tired once it grows tedious enough. So, I'm going to try to make my questions as specific as possible.

First thing that jumped out at me is this:

In regards to inflation, an Austrian will likely say that we have had massive inflation. The Austrian defines inflation as an increase in the money supply. I think you are referring to "price inflation" or the Quantity Theory of Money. The Austrians are not alone in supporting this theory in general. I think only Keynesians and perhaps Mercantalists would challenge that theory.

You're right that I'm referring to price inflation -- because that's the kind that seems to have a concrete effect on people. Why would we worry about the other kind of inflation, if it doesn't affect prices? What concrete negative outcomes does your economic theory predict for increasing the money supply? And are you then concretely saying that you reject a strong link between increasing the money supply and price inflation, and that the last few years have disproved those who expected high price inflation?

In regards to Europe vs US, yes, I'm saying that these economies responded differently to the 2008 crisis, that Europe cut government spending more sharply than the US did, that we can observe the European recovery has been poorer, and that this suggests a correlation. I take it you disagree - with what, specifically?

On Greece, yes they have a history of economic mismanagement, but again, we see observe a correlation between the sharp cuts in government spending and the sharp jump in their unemployment rate. What are your views on the causal relationship between government spending and unemployment? I don't see how you argue that more spending creates unemployment, since the observable facts in Greece indicate otherwise. I could see you making an argument that spending doesn't reduce unemployment, but I don't know how specifically you would argue that. Or maybe you think there is no causal relationship?

Just as those who claimed we were going to be the next Greece were wrong, because we're two extremely different countries, those who say we can use Greece as a cautionary tale are, IMHO, similarly misguided.

PVW said:

As long as definitions are fluid, it's impossible to be wrong -- you can just claim that what I call libertarianism isn't how you define it, and we can haggle back and forth and eventually just get bored or tired once it grows tedious enough. So, I'm going to try to make my questions as specific as possible.

First thing that jumped out at me is this:

In regards to inflation, an Austrian will likely say that we have had massive inflation. The Austrian defines inflation as an increase in the money supply. I think you are referring to "price inflation" or the Quantity Theory of Money. The Austrians are not alone in supporting this theory in general. I think only Keynesians and perhaps Mercantalists would challenge that theory.You're right that I'm referring to price inflation -- because that's the kind that seems to have a concrete effect on people. Why would we worry about the other kind of inflation, if it doesn't affect prices? What concrete negative outcomes does your economic theory predict for increasing the money supply? And are you then concretely saying that you reject a strong link between increasing the money supply and price inflation, and that the last few years have disproved those who expected high price inflation?

In regards to Europe vs US, yes, I'm saying that these economies responded differently to the 2008 crisis, that Europe cut government spending more sharply than the US did, that we can observe the European recovery has been poorer, and that this suggests a correlation. I take it you disagree - with what, specifically?

On Greece, yes they have a history of economic mismanagement, but again, we see observe a correlation between the sharp cuts in government spending and the sharp jump in their unemployment rate. What are your views on the causal relationship between government spending and unemployment? I don't see how you argue that more spending creates unemployment, since the observable facts in Greece indicate otherwise. I could see you making an argument that spending doesn't reduce unemployment, but I don't know how specifically you would argue that. Or maybe you think there is no causal relationship?

I was just trying to clarify. This reminds me of when you discuss Capital with Keynsians. They see Capital as one big uniform blob. But, its not. Nor are Libertarians one big uniform blob. And, I'd say that definitions are important.

In regards to the definition of inflation, I will quote the late great Henry Hazlitt:

Now obviously a rise of prices caused by an expansion of the money supply is not the same thing as the expansion of the money supply itself. A cause or condition is clearly not identical with one of its consequences. The use of the word "inflation" with these two quite different meanings leads to endless confusion.

The word "inflation" originally applied solely to the quantity of money. It meant that the volume of money was inflated, blown up, overextended. It is not mere pedantry to insist that the word should be used only in its original meaning. To use it to mean "a rise in prices" is to deflect attention away from the real cause of inflation and the real cure for it.

In Regards to your question about if Monetary Inflation causes Price Inflation, it sure does. But again, this is a complicated discussion. First, it has caused price inflation. As I've pointed out, there are many asset categories that are at all time highs. That is price inflation.

I'm sure you're asking yourself. But what about the CPI? It's been between 0 and 2%! This guy doesn't know what he's talking about! I think the thing to remember is that the CPI tracks a basket of goods chosen by the BLS. This does not include things like stock prices, Housing Prices, etc. That is why the CPI didn't explode when Housing Prices were clearly exploding.

In addition, each element of the CPI is weighted. Weights are adjusted as prices move. For example, if meat increases in price then it's weight in the CPI will decrease, and that weight will apply to another good that is likely to be substituted. So, if you could be eating more Ramen noodles because meat increased in price, but that doesn't mean inflation as measured by the CPI has increased. There are also hedonic adjustments that adjust prices lower due to increased quality. To say the least, this is an imperfect statistic.

And why should people care absent price inflation as defined by the CPI. There are numerous reasons. First, if you are interested in buying a house, and house prices are increasing due to public policy including monetary inflation, you are being hurt by this policy. But perhaps the biggest reason that people should care about monetary inflation is that it is the primary driver of the business cycle. Monetary Inflation and its accompanied low interest rates disrupt the price mechanism(it is a form of price fixing after all). This essentially is the root cause of bubbles. We saw drastic monetary inflation during the formation of the tech bubble, during the formation of the housing bubble, and we are seeing it again.

There are even terms for this. The "Greenspan Put" for instance. If you think the Fed has your back, are you more or less likely to take risks? If the money you keep in the bank is going to be inflated away at a higher rate than you earn interest, are you going to make your portfolio more or less risky? We have had ZIRP for 7 years. How is one to save in this environment? People who are not equipped to navigate the markets are being thrown to the wolves.

Regarding Greece, it is a different country than the US. However, an economy that takes on too much debt will always face a day of reckoning. In that way, Greece is a great example for the entire west. I'm not sure what your point is about spending and unemployment. But I'm puzzled that you seem to be asserting that countries or really any entity can spend money it does not have and cannot borrow.

The problem with having large amounts of unproductive government employees is that they have to be paid for. While you are giving these people money and they spend it, things are great. But, someone has to pay for this as the government does not have any money. They can tax or borrow money. If they tax, they are taking money from one person and giving it to another. I'm not sure how this creates additional prosperity. If they borrow, the money has to be financed. This can become a burden. In the case of Greece they went broke.

I actually think its hilarious that Greece over spent and lied about its finances for years and years. Their ability to borrow was seriously curbed, and really only kept afloat through the kindness if its EU neighbors. But the problem after they go broke is Austerity!

Thanks for the lengthy response. I'm having a hard time matching your theory to what actually happened, though. Well, actually first, I want to note a huge problem I have with your definition of inflation:

[CPI] does not include things like stock prices, Housing Prices, etc. That is why the CPI didn't explode when Housing Prices were clearly exploding.

There's certainly reasonable arguments to be had as to whether we are including the right goods in our CPI "basket," but if you're including stock as a marker of inflation, it seems a pretty worthless marker. Anytime the stock market is doing well, that's inflation? You might call it inflation, but most people call it seeing your assets increase in value, generally regarded as a good thing and the whole point of investing!

Tempting as it is to get into an argument over this, though, I think that's actually not the meat of where we disagree. Here we go:

This essentially is the root cause of bubbles. We saw drastic monetary inflation during the formation of the tech bubble, during the formation of the housing bubble, and we are seeing it again.

I'm not sure I understand what you're claiming here. We agree that during the response to the crisis, via the stimulus, QE, etc, the federal government pumped a lot of money into the economy. They weren't doing anything on that scale during the housing crisis, so I really don't know what you mean here. You want to blame the housing crisis on monetary "inflation," but clearly there's a difference in both scale and, I would argue, in kind, between pre and post 2008 monetary policy. You seem to just wave that difference aside here, which I don't think you can, and I'd like to press you on that.

On Greece, I picked it out as an example of where what you would like to see happened, and happened on a dramatic scale -- large cuts in government spending. Greece isn't the only example -- Europe as a whole cut spending far more than the US did in response to the crisis. If you don't like the example of Greece, we could also look, for instance, at the UK. Across a variety of countries, with different levels of good or poor histories of fiscal management and debt-to-gdp ratios, we see that their recovery has been poorer than ours. What I see in common is steeper cuts to government spending than we did.

Perhaps you have a good counter-example to offer -- an economy that found itself in crisis and successfully embraced austerity as a way out? We can offer as many theories as we like, and they can all sound plausible, but I think concrete examples are much more clarifying.

PVW said:

Thanks for the lengthy response. I'm having a hard time matching your theory to what actually happened, though. Well, actually first, I want to note a huge problem I have with your definition of inflation:

No problem on the response. Brevity has never really been my thing. ;-)

There's certainly reasonable arguments to be had as to whether we are including the right goods in our CPI "basket," but if you're including stock as a marker of inflation, it seems a pretty worthless marker. Anytime the stock market is doing well, that's inflation? You might call it inflation, but most people call it seeing your assets increase in value, generally regarded as a good thing and the whole point of investing!

The CPI is a complex measurement. And I look at it with a great deal of skepticism. I wouldn't say that the stock market increases are price inflation per se. However, I would posit that there are 2 causes of a general stock market increase. Production/profit increases & monetary inflation. I would agree that part of the point of investing is to see an increase in stock prices, but I would think that the other part is to get cash flow from your investments(in stocks this would be dividends). Minus the cash flow part it seems quite a bit like speculation. I mean, for a while people looked like absolute geniuses for buying Pets.com.

I'm not sure I understand what you're claiming here. We agree that during the response to the crisis, via the stimulus, QE, etc, the federal government pumped a lot of money into the economy. They weren't doing anything on that scale during the housing crisis, so I really don't know what you mean here. You want to blame the housing crisis on monetary "inflation," but clearly there's a difference in both scale and, I would argue, in kind, between pre and post 2008 monetary policy. You seem to just wave that difference aside here, which I don't think you can, and I'd like to press you on that.

You're right in that there was no Quantitative Easing prior to the bubble. However, that does not mean there was no Monetary inflation. See the M3 chart below. During both the tech bubble and the housing bubble, monetary policy was extremely loose. We had negative real interest rates for long stretches of time.

The reason you are seeing QE, Operation TWIST, and talk of even more radical monetary tactics like negative interest rates(and the accompanied limits on cash), the trillion dollar coin nonsense, etc. is that Central Banks are struggling to create inflation. These are just more radical policies meant to cause inflation. IMO, this should have us worried. These policies have been in place for what 7 years now? And still we have the look of a sick economy.

PVW said:

On Greece, I picked it out as an example of where what you would like to see happened, and happened on a dramatic scale -- large cuts in government spending. Greece isn't the only example -- Europe as a whole cut spending far more than the US did in response to the crisis. If you don't like the example of Greece, we could also look, for instance, at the UK. Across a variety of countries, with different levels of good or poor histories of fiscal management and debt-to-gdp ratios, we see that their recovery has been poorer than ours. What I see in common is steeper cuts to government spending than we did.

But as has been pointed out. Greece's situation is very different from ours. Greece was further along the path that America is. Greece cannot print its own currency. Furthermore, even if they could, their currency is not seen as the global reserve currency. They were broke. We will go broke too if we stay on the current path. If and when this happens, will our crisis manifest itself in a different way then Greece's? Probably.

It's important to remember, when any entity(country, business, individual, etc) runs up debt it needs to be financed and serviced in some way. As you add debt, this becomes more difficult. At some point it becomes impossible. Things that don't seem to matter for a long time sometimes matter quite a bit all of a sudden. It's funny that when you most need to borrow money, often there's no one to lend it to you.

America has always had a much more dynamic economy than the European nations. I don't think we are on equal footing. I personally think the Austerity argument is overblown, because almost nobody practiced what I would call Austerity. The type of austerity they are talking about is slowing debt growth down slightly. Seems like we're trying to redefine another word.

Perhaps you have a good counter-example to offer -- an economy that found itself in crisis and successfully embraced austerity as a way out? We can offer as many theories as we like, and they can all sound plausible, but I think concrete examples are much more clarifying.

That's an interesting example, not least because I was unaware of it. I'd been hoping to have more time to read about it, but since it's now been a few days, I'll just post my off-the-cuff initial thoughts in the interests of not letting this thread go too stale.

So my first impression is that this seems rather to fit in with my understanding of economics (which I guess is keynesian). If you were to ask me, what would happen if the federal government slashed spending, I'd guess you'd get a recession. If you were to then ask, what would happen if in the midst of the recession it took a tight monetary policy, I'd guess you'd run the risk of triggering deflation and seriously deepening the severity of the recession. And that seems to be what happened here.

Fighting a war is very economically stimulating, when you're a) on the winning side and b) your own territory is in no danger itself (if your territory is being fought over, the destruction of infrastructure and other assets is probably going to outweigh and stimulative effects from increased spending). So the war ends, and we expect a slowdown. Not only that, but then we drastically cut our armed forces, so basically the nation's largest employer suddenly lays off millions of workers. Austerity!

That's my initial reaction. I'd guess the counterargument would be that the recession would have been longer had the government engaged in stimulus. I'd be curious if, say, Canada had a parallel experience we can compare against? (comparing to 1920-21 Europe wouldn't be too helpful as the war destroyed a lot of property/capital there, so not really an apples-to-apples comparison).

TylerDurden said:

Exactly. I'm asking what the solutions are. I don't see where I've offered solutions on this thread.

I only get "We need to spend more!" I get it. $18 Trillion in Federal Debt with a large number of States and local Municipalities in very tenuous financial condition is not enough.

I'm simply asking: "How much would be enough?" Is it $19 Trillion? $20 Trillion? $50 Trillion? $200 Trillion? Exactly how should we spend that money and how will that get us back on a good economic path where we can leave things better rather than worse for posterity?

If one advocates "More!!!" as a general policy, but won't even take a stab at answering the above questions I would be careful about throwing around terms like "stupid" or "theological arguments" unless there is a mirror staring you in the face.

I don't know how much is enough. Sadly, if we increase spending there will be much waste. I don't know if we'll get that bang for the bucks considering how well cronyism and corruption have embedded in our society.

The debt may be 18 trillion but after WW2 the debt was 30 trillion in current dollars. We did very well after that war while having had that debt.

Money is cheap now.

We’re living in a world awash with savings that the private sector

doesn’t want to invest, and is eager to lend to governments at very low

interest rates. It’s obviously a good idea to borrow at those low, low

rates, putting those excess savings, not to mention the workers

unemployed due to weak demand, to use building things that will improve

our future.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/23/opinion/keynes-comes-to-canada.html

PVW said:

That's an interesting example, not least because I was unaware of it. I'd been hoping to have more time to read about it, but since it's now been a few days, I'll just post my off-the-cuff initial thoughts in the interests of not letting this thread go too stale.

So my first impression is that this seems rather to fit in with my understanding of economics (which I guess is keynesian). If you were to ask me, what would happen if the federal government slashed spending, I'd guess you'd get a recession. If you were to then ask, what would happen if in the midst of the recession it took a tight monetary policy, I'd guess you'd run the risk of triggering deflation and seriously deepening the severity of the recession. And that seems to be what happened here.

Fighting a war is very economically stimulating, when you're a) on the winning side and b) your own territory is in no danger itself (if your territory is being fought over, the destruction of infrastructure and other assets is probably going to outweigh and stimulative effects from increased spending). So the war ends, and we expect a slowdown. Not only that, but then we drastically cut our armed forces, so basically the nation's largest employer suddenly lays off millions of workers. Austerity!

That's my initial reaction. I'd guess the counterargument would be that the recession would have been longer had the government engaged in stimulus. I'd be curious if, say, Canada had a parallel experience we can compare against? (comparing to 1920-21 Europe wouldn't be too helpful as the war destroyed a lot of property/capital there, so not really an apples-to-apples comparison).

No worries on taking time to respond. I'm pretty sure most of us have jobs, kids, or what have you. Life gets pretty busy. We don't always have time to discuss economic policy w/ the town libertarian crank ;-)

The lesson I draw from 1921 vs the Great Depression of the 1930's is that bad things happen if we don't let the price mechanism to work. What you saw in 1921 was a sharp, but brief recession due to the transition of an economy structure to feed the war machine to an economy that is set up to provide goods and services to the people. The resources were not allocated properly for the economy. There were inventories of goods that there was not a lot of demand for. It takes some time for those resources to be re-allocated. However, when this process is allowed to take place, the economy is able to get back on a prosperous path before too long. In 1921 we allowed that process to run its course.

==> Far from boosting spending, the federal government (under Wilson/Harding) slashed spending 82 percent over three years (that’s not a typo), going from $18.5 billion in Fiscal Year 1919 to $3.3 billion in FY 1922.

==> Far from easing, the Fed engaged in literally unprecedented tightening, with discount rates rising to all-time highs (since the founding of the Fed) and with the monetary base collapsing some 15 percent year/year (though that’s using the seasonally adjusted data, so some may quibble with the figure).

==> Prices fell more rapidly in one year than at any 12-month span during the Great Depression. From its peak in June 1920 the Consumer Price Index fell 15.8 percent over the next 12 months. In contrast, year-over-year price deflation never even reached 11 percent at any point during the Great Depression.

==> Far from being “rigid downward,” nominal wages fell 20 percent in a single year, according to Vedder and Gallaway.

Another interesting example of this phenomenon is after World War 2. Most prominent Keynesians felt that we were going to go right back into the Great Depression if we significantly lowered Federal Spending. From the Mercatus Center:

The standard thinking of the day was that the United States would sink into a deep depression at the war’s end. Paul Samuelson, a future Nobel Prize winner, wrote in 1943 that upon cessation of hostilities and demobilization “some ten million men will be thrown on the labor market.”[3] He warned that unless wartime controls were extended there would be “the greatest period of unemployment and industrial dislocation which any economy has ever faced.”[4] Another future Nobel laureate, Gunnar Myrdal, predicted that postwar economic turmoil would be so severe that it would generate an “epidemic of violence.”[5]

This, of course, reflects a world view that sees aggregate demand as the prime driver of the economy. If government stops employing soldiers and armament factory workers, for example, their incomes evaporate and spending will decline. This will further depress consumption spending and private investment spending, sending the economy into a downward spiral of epic proportions. But nothing of the sort actually happened after World War II.

In 1944, government spending at all levels accounted for 55 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). By 1947, government spending had dropped 75 percent in real terms, or from 55 percent of GDP to just over 16 percent of GDP.[6] Over roughly the same period, federal tax revenues fell by only around 11 percent.[7] Yet this “destimulation” did not result in a collapse of consumption spending or private investment. Real consumption rose by 22 percent between 1944 and 1947, and spending on durable goods more than doubled in real terms. Gross private investment rose by 223 percent in real terms, with a whopping six-fold real increase in residential- housing expenditures.[8]

The private economy boomed as the government sector stopped buying munitions and hiring soldiers. Factories that had once made bombs now made toasters, and toaster sales were rising. On paper, measured GDP did drop after the war: It was 13 percent lower in 1947 than in 1944. But this was a GDP accounting quirk, not an indication of a stalled private economy or of economic hardship. A prewar appliance factory converted to munitions production, when sold to the government for $10 million in 1944, added $10 million to measured GDP. The same factory converted back to civilian production might make a million toasters in 1947 that sold for $8 million—adding only $8 million to GDP. Americans surely saw the necessity for making bombs in 1944, but just as surely are better off when those resources are used to make toasters. More to the point, growth in private spending continued unabated despite a bean-counting decline in GDP.

As figure 1 shows, between 1944 and 1947 private spending grew rapidly as public spending cratered. There was a massive, swift, and beneficial switch from a wartime economy to peacetime prosperity; resources flowed quickly and efficiently from public uses to private ones.

Just as important, the double-digit unemployment rates that had bedeviled the prewar economy did not return. Between mid-1945 and mid-1947, over 20 million people were released from the armed forces and related employment, but nonmilitary-related civilian employment rose by 16 million. This was described by President Truman as the “swiftest and most gigantic change-over that any nation has made from war to peace.”[9] The unemployment rate rose from 1.9 percent to just 3.9 percent. As economist Robert Higgs points out, “It was no miracle to herd 12 million men into the armed forces and attract millions of men and women to work in munitions plants during the war. The real miracle was to reallocate a third of the total labor force to serving private consumers and investors in just two years.”[10]

Oh, and Yes, that is the same Paul Samuelson who probably wrote your Economics Text Book, and who touted the Soviet Union Economy in 1989.

That's a bit of a circular argument though, isn't it? After all, it was massive state intervention, in the form of WWI, that inflated the money supply prior to that recession, and arguably (or at least I would argue) that it was the subsequent sharp cutting in that spending that led to the recession. That seems a different situation from the 1930s - 1950s, when you're going from a period of deep economic depression into massive spending (WWII) and then you end up with an entire continent needing consumer goods and pretty much only us able to supply them. It also seems very different from 2008, when the recession came from a precipitous collapse in private sector spending, not government spending.

In sum, I'd say the cause of the economic drop is important, and ought to guide the response. I suspect that a more graduated discharging of soldiers after WWI, or perhaps continuing the pay of soldiers for some time after discharge, would likely have avoided the 1920 recession since the cause of it was the sudden shut off of government spending. And in 2008, stimulus was needed to make up for the collapse in private spending.

I should clarify that in normal times, I'm not really in favor of deficit spending -- all things being equal, I think taxes/gov revenue in general should be high enough, and spending low enough, to even out (though what we choose to spend on is I think a value judgment, not an economic one). In times of crisis, though, it really seems that the theory that government can step in to make up for drops in private spending is fits the observed facts.

BTW, happy birthday to, uh, Terp? ;-)

Just to clarify - what I see circular is arguing that the solution to a recession caused by sharply cutting government spending is cutting government spending.

PVW said:

That's a bit of a circular argument though, isn't it? After all, it was massive state intervention, in the form of WWI, that inflated the money supply prior to that recession, and arguably (or at least I would argue) that it was the subsequent sharp cutting in that spending that led to the recession. That seems a different situation from the 1930s - 1950s, when you're going from a period of deep economic depression into massive spending (WWII) and then you end up with an entire continent needing consumer goods and pretty much only us able to supply them. It also seems very different from 2008, when the recession came from a precipitous collapse in private sector spending, not government spending.

In sum, I'd say the cause of the economic drop is important, and ought to guide the response. I suspect that a more graduated discharging of soldiers after WWI, or perhaps continuing the pay of soldiers for some time after discharge, would likely have avoided the 1920 recession since the cause of it was the sudden shut off of government spending. And in 2008, stimulus was needed to make up for the collapse in private spending.

I should clarify that in normal times, I'm not really in favor of deficit spending -- all things being equal, I think taxes/gov revenue in general should be high enough, and spending low enough, to even out (though what we choose to spend on is I think a value judgment, not an economic one). In times of crisis, though, it really seems that the theory that government can step in to make up for drops in private spending is fits the observed facts.

BTW, happy birthday to, uh, Terp?

Well they are all different, but they rhyme. I would contend that we should look more at what was happening prior to the depressions rather than how to mop up subsequent to the correction. I also think that we should be careful that we focus on the health of the economy and not focus on one metric.

For example, people will contend that WWII pulled us out of the Great Depression. They will point to the GDP growth as proof of this contention. But remember, government spending is counted as part of this metric. So, although that metric was increasing during WWII, we had price controls, rationing, etc. These are not economic conditions anyone here is likely to want to live under.

And remember, the massive government interventions didn't start in WWII. We already had a decade of radical interventions prior to entering the war.

You see similar mistakes made touting a low unemployment rate, even though that metric is often quite misleading.

Lets look at the economic cycles mentioned on this thread.

- 1921 depression: Caused by the WWI economy adjusting back to a civilian economy. The government reaction is to lower spending back to normal rates. The result is a sharp, but brief recession followed by economic growth.

- Great Depression: caused by a mania in equities predictably caused by a credit expansion in place to facilitate an effort by Britain to peg their currency to a too high a level of gold. The government response included unprecedenet intervention including price/wage fixing, trade controls, massive government works programs, crop destruction, gold confiscation, etc. The result is a deep prolonged economic depression lasting over a decade.

- Post WWII: Caused by WWII economy adjusting back to a civilian economy. The government appropriately cut the unneeded military spending against the protests of prominent Keynesians. The result is the much ballyhooed post-war expansion.

- Technology Bubble: Caused by a mania in equities caused by an enormous credit boom facilitated by Federal Reserve policy. The result was a severe recession. The resonse was a continuation of negative real interest rates marching in the age of the housing bubble. Coincidentally, this coincided with the development of the War on Terror that includes multiple foreign wars and the constuction of a massive homeland security apparatus. The result was a continuation of economic growth by most aggregates, but also even more radical monetary policy.

- Housing Bubble: massive credit growth never before seen in the history of mankind brings in an era of financial engineering designed to hide risk brings about a highly leveraged system. A housing bubble (asked for by Pimco bonds and cheered on by Paul Krugman) ensues. The popping of the housing bubble brings the world financial system to its knees. The response is massive bailouts coupled with unprecedented radical monetary policy by Central Banks across the globe. These policies are still in place to this day. As a result, the financial system continues to lever up as debt growth continues at an astounding rate.

I'm not sure I see a stellar track record for government intervention there.

PVW said:

Just to clarify - what I see circular is arguing that the solution to a recession caused by sharply cutting government spending is cutting government spending.

Here's why its not circular. The recession is not caused by the cut in government spending. It is caused by thepolicies that precede the recession. In the cases of war, it is no longer appropriate to use resources on the military at those levels after the war. In a bubble we are inappropriately allocating resources on pets.com or on housing projects(or the financing of these projects) that are not desired at the bubble levels. These misallocated resources must be reallocated to more appropriate uses. This is the cause of the recession. If the adjustment is allowed to take its course, then the economy will heal. If not, the economy will suffer.

Capitalism doesn't work without failure. Some companies need to fail in order for the resouces to be put to a more productive use. This process benefits us all in the form of better products at cheaper prices. Asking the government to continue War spending when no longer needed is like asking to continue funding buggy whip companies after the introduction of the automobile.

Thanks for the birthday wishes

Those are some pretty simple explanations you got there. It would be a much more comforting world if events with huge implications could be explained by one or two carefully selected factors.

tom said:

Those are some pretty simple explanations you got there. It would be a much more comforting world if events with huge implications could be explained by one or two carefully selected factors.

And here I am thinking this is a message board and not a PHD Thesis. Occam's razor and all that. Why don't you clarify the causes there big guy?

A little less emphasis on the fault of government intervention and the Fed; a little more on those engaging in the various credit manias.

That's all.

tom said:

A little less emphasis on the fault of government intervention and the Fed; a little more on those engaging in the various credit manias.

That's all.

People act crazy during manias. It happens all the time. The riddle is: Why did everyone simultaneously lose their mind? I think its a stretch to say it was just one big coincidence.

Sponsored Business

Promote your business here - Businesses get highlighted throughout the site and you can add a deal.

For Sale

-

2007 Honda Fit $4,400

More info

No, I said nothing of the sort about following a "plan" that would guarantee a perfectly working economy (hmm, and what would that be?) Ideologically driven beliefs like that are reserved for Austrians and Capitalists.

That doesn't mean that more could not be done. You keep on prattling on (and I say prattle because you've been repeating the same line for a good 5 years now) "well, you've already had your stimulus. how much more do you want?"

More than what we've done. A lot more, since we've done the opposite of nothing since the original stimulus. Not only have we not gone for more stimulus, but the government actually retracted (though not as badly as Europe) in the ensuing years.

There's all this damn evidence, years of it. Multiple countries. Different approaches. And yet you seem to disregard all of it.